Although UX is not a new concept and has existed for a long time, it took time to evolve into what it is now. In the initial stages, it primarily started as a technique for arranging and organizing objects. The tools and jobs people had at the time were fundamental, and they didn’t have the luxury of technology to implement grand schemes. With the advancement in production capabilities, people started designing systems of functionality that helped make workplaces more suitable for the employees so that productivity could increase.

Later, in the technological era, the concept reached its essence and was used to optimize the end user’s experience of products and services, i.e., the general public. In the digital realm, too, the focus was primarily on interface alone and improving it to users’ taste. This practice changed when Cognitive Psychologist and Designer Donald Norman coined the term User Experience. He changed his job title from “User Interface Architect” to “User Experience Architect” to emphasize that the focus should not be limited to designing the interface.

Norman studied the human mind until 1988 when he wrote his book “The Design of Everyday Things.” He states that he wrote the book to express his contempt over how simple things that we use every day distract us and confuse us because they are not optimized enough. He says in his book that he, like many of us, has issues with figuring out how to open a door. Not surprising at all. There are too many kinds of doors: doors that you pull, doors that you push, doors that you slide, doors you lift, uff.

After he wrote the book, he says he got into product development and entered the computer making industry. And over time, he infamously changed his job title to make space for the term User Experience.

The evolution of UX design through history is essential to understand the path it is likely to take in the future. So, let’s take a look at how it all started.

Table of Contents

ToggleBack to BC

The Chinese had a system called “Feng Shui,” a spatial arrangement technique, where they arranged things to utilize the energy of the natural elements optimally. This system was in practice as early as 4000 BC. The concept gave importance to order and organization and is considered the earliest form of UX design.

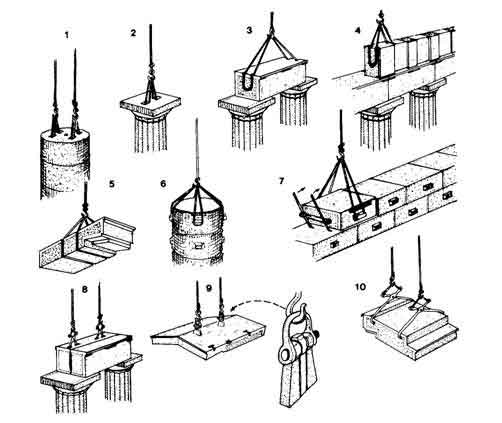

The Greeks, too, had a system called “Ergonomics,” which dates back to 500 BC. This system was more evolved than Feng Shui, as it focused on more than just the flow of natural elements when arranging things. It involved studying usability and human interaction with relation to objects. And it covered more than just the arrangement of objects and extended further.

Ergonomics is essentially a guide for best practices at a workplace to ensure a smooth flow of productivity. In recent centuries, the term became popular through the book “An outline of Ergonomics or The Science of Work” by Polish Scholar Wojciech Jastrzębowski in 1857.

An example for the applications of Ergonomics would be the design for the optimal arrangement of surgical tools for a surgeon in that the surgeon is not intruded by the positioning of the tools, and also finds it convenient to access them when he needs them, suggested by writer and historian, Herodotus.

Industrial development and UX

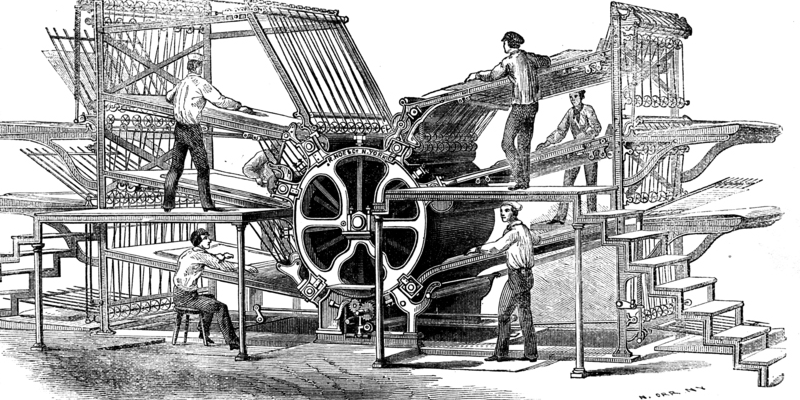

The industrial age took things a little further and started implementing entire systems to improve workplace efficiency.

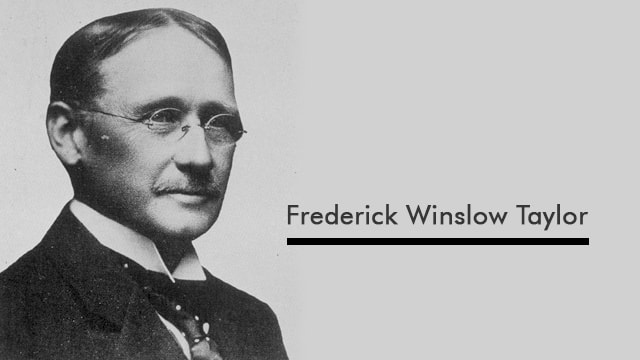

The efforts of Frederick Winslow Taylor in the early 1900s brought significant improvements in workplace management. He was a strategic manager at a factory, and he wrote a book named “The Principles of Management” in 1911.

In his book, he shares experiments that he conducted to ascertain the optimal productivity of labourers and how he used that data to distribute work. He talks about how he focused on solving employee problems because he believed that employee satisfaction hugely impacts the organization’s growth.

Automakers like Toyota and Ford applied similar principles and revolutionized how their factories functioned. Ford wasn’t the first to do it, but the company made conveyor belts famous in that era. Ford took inspiration from the early designs of similar machines by the artist/inventor Leonardo Da Vinci. The use of conveyor belts changed the way factories assembled parts and did the packaging.

Technology and UX

UX is often associated with technology and the digital world because the tech giants adopted the concept in their early stages. Companies like IBM, Apple, and Xerox had high esteem for UX design, and they practically normalized the importance given to the concept.

Henry Dreyfuss, who worked with the “Human Factors” wing of IBM, wrote a book titled “Designing for People” in 1955. His wing worked to improve the usability of the company’s products. He believed that, as a designer, he fails when the end-user senses friction with the product. His thought was that the success of a design lies not just in the product delivering its purpose but also in the user feeling comfortable using it.

The Xerox company had a famous research wing, PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), that enabled users with technology that was easier to use. In collaboration with Apple, the company developed the graphical user interface and the mouse, among other things. The company pretty much created the foundation for modern computing. The focus was to optimize the technological interface to its best ability.

And then Donald Norman came and took the term User Interface and expanded it into User Experience and made it a matter of discussion.

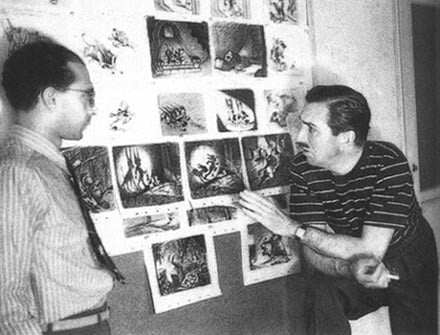

Walt Disney and UX

Walt Disney and his enthusiasm for delighting his customers were probably the first traces of businesses focusing on customer satisfaction quite seriously. He went beyond his way to deliver near-perfect experiences to those who came to the “Disneyworld” and paid attention to the tiniest of details. He was one of the earliest minds to go beyond delivering the purpose with his products and services and focus on customer satisfaction.

Disney believed that any technology has to evolve constantly, and any service has to be regularly improvised. He didn’t want his customers to feel they had seen all that Disney could offer them. Disney urged his team to collect consumer behavior data and make lists of problems or distractions they face. He came up with solutions that rectified this behavior that reduced his business.

He wanted to present everything clearly in simple verbal and visual cues. He didn’t want his customers to feel exhausted by the intellectual effort in consuming his services. Disney passionately advocated the importance of fun and relaxation. He hated approaching things with a rigid and financial perspective.

His vision for his Disneyworld, and everything his brand did, was to satisfy the people who pay for his services emotionally. That pretty much sums up the essence of what UX is. It won’t be an exaggeration to call him the first-ever UX designer.

UX now

The term UX design, which has become increasingly popular in the present era, often gets restricted to the digital realm. It’s a common perception that UX design is only about designing applications, software, and websites. This thinking may be because most non-digital industries have been having UX designers (or something close to that) in some other titles and positions, possibly with additional responsibilities.

For example, industrial design is a job profile that comes close to UX design. Architecture shares a lot of similarities with UX Design. In their own industries, with their own distinct features, these can be compared to UX design.

And hence, the term UX Design is, presently, predominantly relevant in the technological zone.